boone trace trail

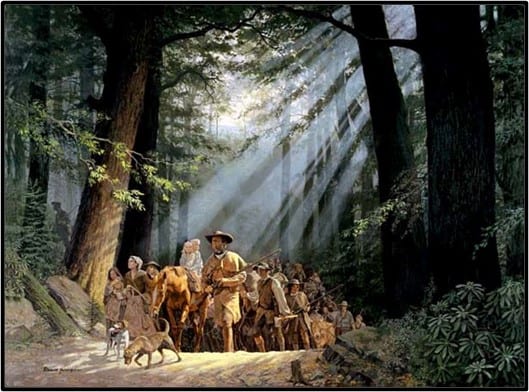

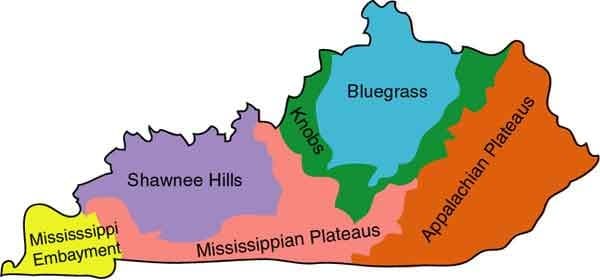

The first white man to come through Cumberland Gap was Christopher Geist, the lead guide and scout for Dr. Thomas Walker and companions, under employment of the Loyal Land Company of Virginia, in 1750. Subsequently, during the months of March and April 1775, Daniel Boone, and a party of 33 trailblazers opened the first road (trail), EVER, for the express purpose of encouraging immigrants to settle the western frontier. Trails developed by herds of buffalo and used by Native American’s (Warrior’s path) and long-hunters (18th-century explorers and hunters), were in existence to guide them through Cumberland Gap, present-day Middlesboro, and Pineville northward. However, Daniel and his crew improved upon those trails and laboriously opened the hardest section of new trail after crossing the Rockcastle River through “the knob’s” physiographic region south of Berea. From there, it proceeded on to Boonesborough on the south bank of the Kentucky River in the outer Bluegrass Region. This trail became the first great gateway to the west – known as Boone Trace.

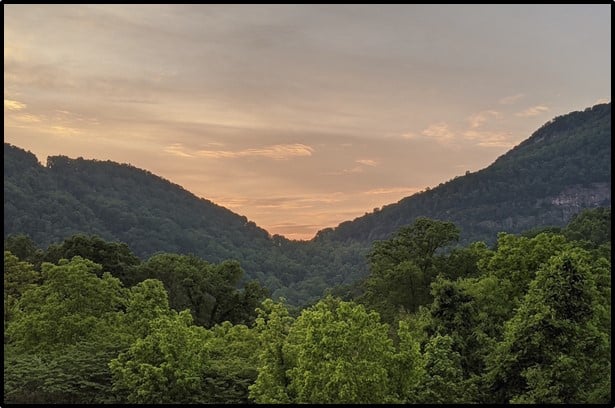

Cumberland Gap

The trail helped establish what was planned to be the 14th colony called Transylvania with its capitol as Boonesborough by Judge Richard Henderson and other investors. This venture succeeded in opening this new land to over 200,000 settlers between 1775 and 1795, that was to become Kentucky, even though the venture was denied by the Colonial Virginia General Assembly in 1778.

Daniel Boone leading immigrants through Cumberland Gap

Painting by David Wright

“That little road” told the world that a person could traverse the wilderness, survive, claim their land, and succeed. It was, therefore hugely important to Kentucky not only becoming a state in 1792, but to the opening of the west.

Richard Henderson, one of the founders of the Transylvania Land Company, had acquired a huge amount of land (approximately 20 million acres) from the Cherokee Indians at the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals in 1775 about 20 miles southeast of Long Island. Henderson then needed a road to bring in settlers to sell off the property for profit; and he hired Daniel Boone to open the road, which at that time was just a dirt bridle path.

Boone was to be given 2,000 acres of land and his coworkers about $50 in today’s dollars in sterling silver, which at that time was equivalent to 400 acres for their trouble, but they never received anything. Little did they know that this narrow trail would initiate the westward movement of hundreds of thousands of settlers to go west and begin a new life of opportunity.

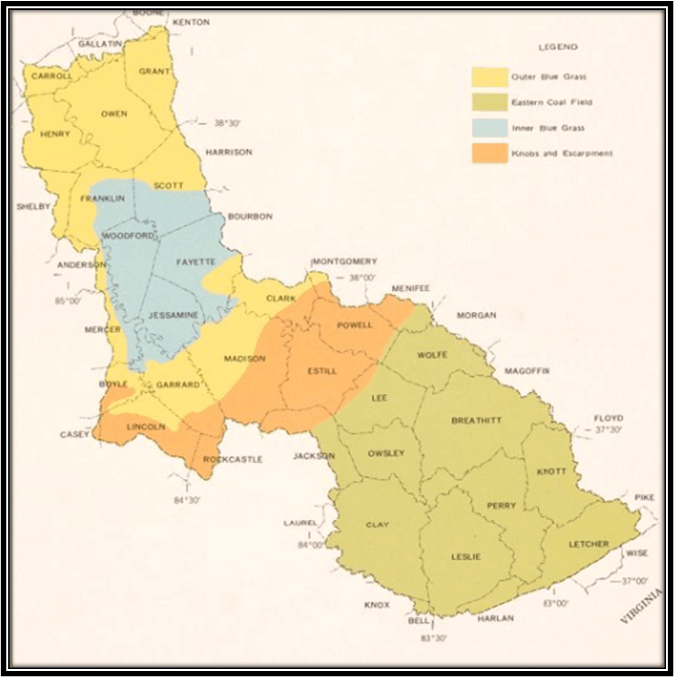

Boone’s journey began at Long Island on the Holston River (present day Kingsport, TN), passed through the Cumberland Gap and north to Boonesborough on the Kentucky River where a fort was constructed, for a total of 258 miles. It passed through Boone Gap just south of where you are now standing and is the last gap or topographic saddle Daniel Boone and his group had to cross to enter the Blue Grass Physiographic Region (see physiographic maps below).

A physiographic region is a large-scale portion of land defined by its distinct geology (the rocks underneath the soil), topography (hills, valleys, and level land) and communities of native plants and animals and history.

As the trail approached present-day Berea, it turned eastward along Brushy Fork Creek. With cooperation between the city of Berea and Berea College, this segment of Boone Trace has been made into a “shared use” path which will connect Slate Lick Road to the Brushy Fork Park and then on eventually to the Pinnacles.

Initially, Boone Trace diverted from this route turning north up Blue Lick Road where it picked up Hays Fork Creek on the way to Twitty’s Fort south of Richmond, KY. Later, it turned north sooner at the confluence of Silver and Brushy Fork Creeks, which can be seen from the bridge on the John B. Stephenson segment of the shared use path.

Be sure to notice, close to the Boone Trace Trail, the remains of a “Wolf Tree” shown below. These trees represent an interesting phenomenon occurring in forests indicating unusual activity in that portion of the forest, such as a road or trail passing through (e.g., Boone Trace?) That opened the canopy for increased sunlight or other natural disturbances (wildfire, windstorms), the native Americans burning of the forest, or pioneers clearing of the surrounding forest for pasture or crops). Usually, the existing forest in that area would have become somewhat “thinned out” and more open (see nearby signage with a QR code that provides an in-depth description of ‘Wolf Trees’).

Another feature along the path will be a short segment, just off the path and closer to the creek, which could be an actual piece of the original Boone Trace (see photo below). If it is not, it represents closely how the actual trail would have appeared. As you stop on this segment of the trail, stand quietly for a few minutes, and you may feel the presence of those brave souls who ventured through the wilderness to begin a new life.